Hunkering Down for the Winter

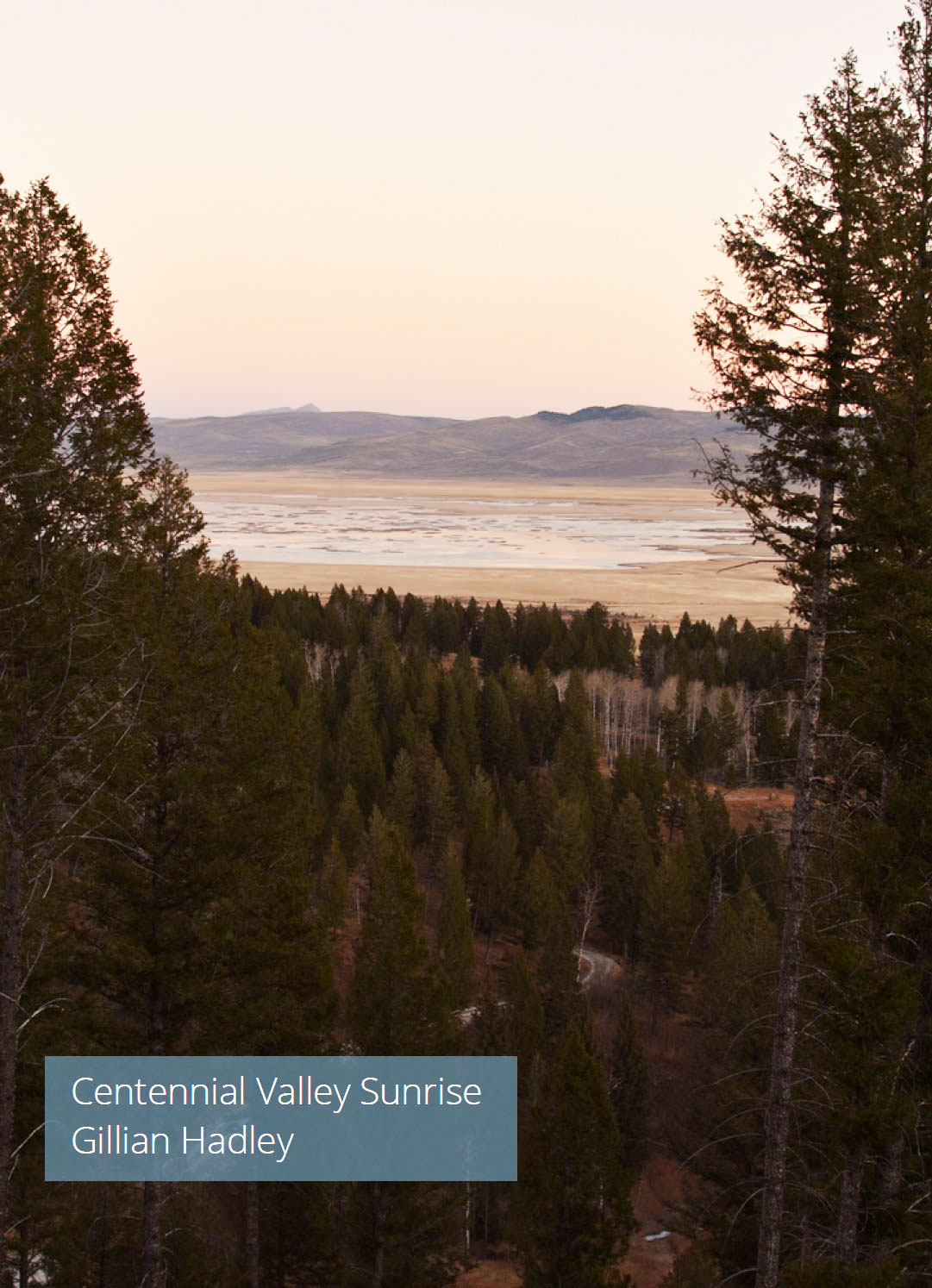

The onset of winter sometimes seems to sneak up on us humans, but other animals are

well prepared. At this point, many have left Centennial Valley. Long-distance travelers

may have already reached their warmer winter destinations. Others, like the pronghorn,

recently moved on to lower elevations nearby where food will be more accessible. Those

that stick around need to contend with the long, cold winter. Some have been stocking

up on food since the summer, building up fat reserves in preparation. They await the

external cues that indicate when they should head to their hibernacula, or hibernation

sites, where they will spend the next few months.

The onset of winter sometimes seems to sneak up on us humans, but other animals are

well prepared. At this point, many have left Centennial Valley. Long-distance travelers

may have already reached their warmer winter destinations. Others, like the pronghorn,

recently moved on to lower elevations nearby where food will be more accessible. Those

that stick around need to contend with the long, cold winter. Some have been stocking

up on food since the summer, building up fat reserves in preparation. They await the

external cues that indicate when they should head to their hibernacula, or hibernation

sites, where they will spend the next few months.

Hibernation is more than a winter-long slumber. It is a form of torpor, a state of drastically reduced metabolic rate used to conserve energy during periods of adverse conditions, such as cold weather and food shortages. Torpor can be short, lasting less than 24 hours, or it can be more long-term, as is the case with hibernation. It is accompanied by reduced respiration and heart rates, as well as a drop in body temperature. Unlike an animal that is merely sleeping, an animal in hibernation may appear to be dead.

Centennial Valley's hibernators include Wyoming ground squirrels, yellow-bellied marmots, little brown bats, and bears. Bears are unusual hibernators, since hibernating animals tend to be on the small side. Smaller animals have higher surface area to body mass ratios. This means they lose heat more quickly than larger animals, and they have higher energy costs for staying warm. For these animals, skipping out on winter altogether is a safe bet.

Wyoming ground squirrels (Urocitellus elegans) can hibernate up to 9 months, entering their burrows as early as July and emerging

around April. Their body temperatures can drop to nearly freezing.

Wyoming ground squirrels (Urocitellus elegans) can hibernate up to 9 months, entering their burrows as early as July and emerging

around April. Their body temperatures can drop to nearly freezing.

Yellow-bellied marmots(Marmota flaviventris) begin hibernating in September, spending the winter in burrows that can be 15 feet under the ground. They will spend up to 8 months hibernating.

Little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) may travel up to 200 miles to their hibernacula, which are usually caves. Hibernating colonies often include thousands of bats. While bats are hibernating, they breathe about once per minute, and their heart rate drops to about 10 beats per minute from their normal 200-300 beats per minute. Like many other small hibernators, their body can reach nearly freezing temperatures.

Bears generally start denning in November, usually following a significant snowstorm. Grizzly bears use their large claws to dig up a new den each year, a process that can take up to a week. Black bears seek out premade dens, sometimes using those made by a grizzly in a previous year. Their dens are lined with bedding materials, such as fir branches or grass, for additional insulation. They will spend about 5-6 months in these dens. Female bears give birth while hibernating.

Super Hibernators

Bears have often not been considered true hibernators. Because of their large size,

they don’t experience the extreme changes in body temperature that are characteristic

of hibernation. Compared to the near freezing temperatures of a bat or ground squirrel,

a bear's 12°F drop in body temperature seems insignificant. But this means they can

react to disturbances more quickly than smaller animals who need to take time to warm

up. Also unlike these other hibernators, who will wake up intermittently, bears can

remain in their dormant state for several months without eating, drinking, or releasing

waste. During this time, waste products like urea get recycled into protein, preventing

muscle atrophy. A hibernating bear's cholesterol levels double without leading to

arteriosclerosis. Bears are also somehow able to retain bone mass and avoid osteoporosis

during this long period of dormancy. These extraordinary physiological feats have

intrigued medical researchers. Many scientists now argue that, not only are bears

true hibernators, they are super hibernators.

Updates from Lakeview Elementary

"Autumn seems to be giving way to winter in the Centennial Valley, with Lower Red Rock Lake frozen up in a late October cold spell that reached -10°F. Most waterfowl have moved further south to find open water, and local children were sighted iceskating on a local pond. Pronghorn have left the Valley for the lower elevation areas nearby where they will spend winter. The high winds recently have the feeling of winter, and a few inches of snow have turned the Valley white again."

Threats to

Hibernating Bats

Bats are vulnerable to white-nose syndrome during hibernation. This disease is caused by a fungus that grows on the face and wings of infected bats. It disrupts their hibernation, causing them to use up their winter energy reserves and ultimately leading to starvation. Millions of bats in North America have died from white-nose syndrome, with little brown bat populations among the most impacted. The disease was first reported in New York state in 2006, and it has been slowly spreading westward each year. The fungus was detected in eastern Montana this year. The exact origin of white-nose syndrome in North America is unknown, but it is thought to have been accidentally introduced by humans.