Winter Forests

Winter Forests

Amidst the tranquil scene of a snow-covered forest, trees are grappling with the challenges of the winter season. Like animals, trees have a variety of tactics for winter survival, each with their own trade offs. Many of these are very apparent, such as the bare branches of deciduous trees. Their leaves' large surface areas are an advantage in the summer but a hinderance in the winter. They lose water to the dry winter air and are very susceptible to ice damage. To save energy, deciduous trees shed their leaves and enter into a dormant state until ideal conditions for photosynthesis return.

Of course, there are always exceptions, and aspens are all-around exceptional trees. Their bark contains chlorophyll, often with a visible greenish tint. While their thin bark makes them more susceptible to pests, it allows them to photosynthesize even without leaves. Photosynthesis carried out by the bark is miniscule compared to that of the leaves, and in the winter it is limited to relatively warm and sunny days. Still, it extends the photosynthesis period for aspens and gives them an advantage for colder climates. This adaptation is part of the reason why aspens are the most widely distributed tree in North America, and can be found growing in otherwise conifer-dominated landscapes.

Conifers are able thrive in high elevation forests thanks to their many adaptations that help them survive harsh weather. Most retain their needles year round. Because of their smaller surface area, these needles don't lose as much water as leaves. They also have a waxy outer coating that further reduces water loss and protects them from damage. Conifers are therefore able to continue to photosynthesize, given suitable water, temperature, and light conditions. When there isn’t sufficient sunlight to carry out photosynthesis, or when temperatures are sustained below freezing, conifers also enter into a dormant state.

Perhaps one of the greatest advantages to retaining their needles is that they extend their growing season, photosynthesizing later into the fall and earlier in the spring than deciduous trees. They also don't need to spend energy growing new leaves each year. Conifers have many other adaptations that help them survive winter, including their typical "Christmas tree" shape. Their flexible, downward facing branches allow for easier snow shed, preventing damage from snow build up.

It is easy to notice these adaptations while wandering through a forest in winter, but many other survival tactics occur out of sight on a microscopic level. Ice formation within cells is a serious threat to plants in freezing temperatures. To avoid damage from ice, both coniferous and deciduous trees will decrease water content and increase sugar concentration in their cells. The highly concentrated sugar acts as an anti-freeze by lowering the cell's freezing point. Ice in a tree's xylem, the water transport system, can also be deadly. While the xylem is made up of cells that are already dead, ice can trap air bubbles and lead to embolism when it thaws. Here, conifers once again have an advantage. The narrow shape of their tracheids, or xylem cells, reduces air bubble formation and the risk of embolism.

Changing Winters

Climate change is bringing a concerning trend of milder winters. In the intermountain west, where so much ecologically and economically relies on winter snow levels, the impacts of this can already be seen. One threat comes in the form of a tiny insect: the bark beetle. Several species of bark beetle are native to western North America, specializing on different tree species. These beetles play a key roles in healthy forest ecosystems, but recent bark beetle population booms are devastating forests throughout the west, and climate change is at least in part to blame for this.

Normally, consistently frigid temperatures help keep bark beetle populations in check. The conditions needed to kill off bark beetles are occurring less frequently because of climate change. This mean more beetles are surviving winter. There are also recorded instances of bark beetles emerging earlier in the spring due to more mild conditions, which in turn can lead to more generations of bark beetles in a year. A decrease in average snowpack further exacerbates the problem. Forests throughout the west depend on snowpack for water supply in the summer. As average snowpack decreases, the risk of drought becomes greater. Since drought-stressed trees are more susceptible to invasions, the threat of bark beetles also becomes greater.

Check out more pictures and videos from Odell Creek, and our other trail talks, on our Instagram page @uofutaftnicholsoncenter. Happy trails!

Updates From Lakeview

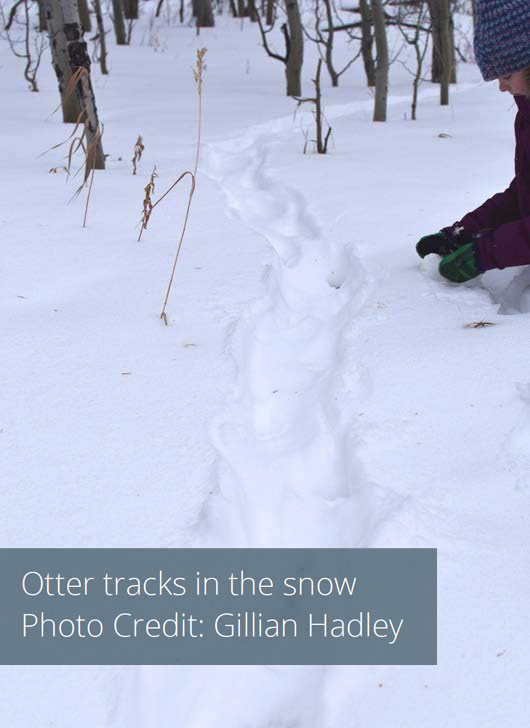

"In late December, we saw the tracks of an animal not usually sighted in Lakeview. The river otter (Lontra canadensis) lives in the lakes and rivers of the Centennial Valley, but doesn’t come near Lakeview very often because there are no large waterways close to town and because of human population. During winter, when lakes and rivers are frozen, otters keeps holes open in the ice so that they can catch fish.

Another animal that is more commonly seen during winter is the ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus). Their scat has been seen recently on ski trails around Lakeview. The grouses’ winter diet is mostly made up of buds and berries."

Contributed by Gillian Hadley, Amelia Warren, and Ivy Warren

Last Call for Artist in Residence Applications

The deadline to apply for our 2021 Artist-in-Residence program is January 31st. This program provides a unique opportunity to spend 2-4 weeks to work on creative projects while immersed in the spectacular landscape of Centennial Valley.

The application and more information about this incredible opportunity can be found on our website.