Surviving the Winter

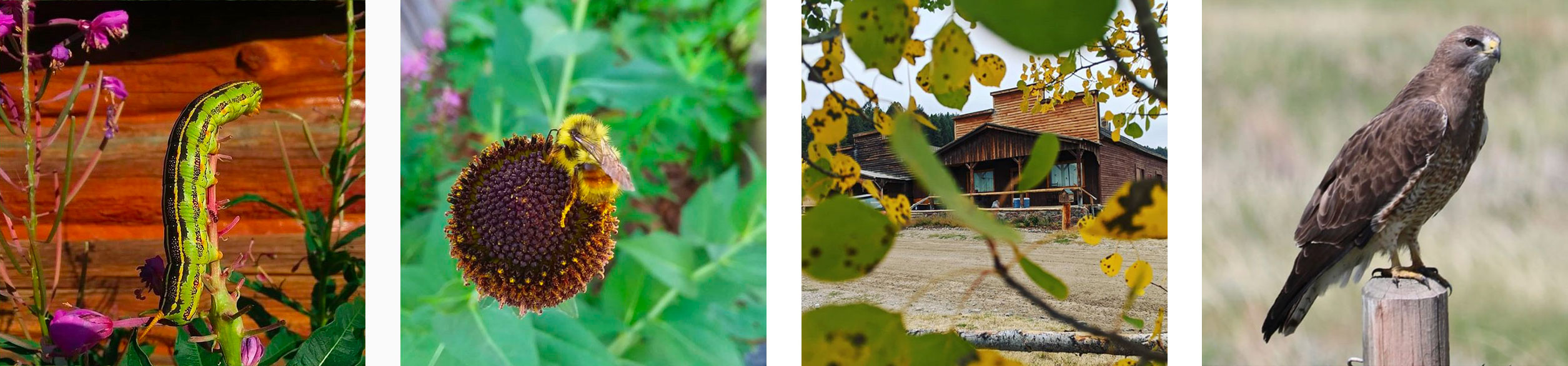

Wildlife that remain active in the winter must be prepared to contend with several feet of snow, extreme temperatures, and food scarcity. What does it take to survive such winters? Here are just a few tactics that these animals use.

Good insulation is key. Many mammals grow a thicker coat for the winter, comprised of long guard

hairs and shorter underfur that is designed to trap air. Birds also have multiple

layers of feathers. As anyone with a down jacket may know, down feathers provide great

insulation, but only when dry. Birds frequently preen their outer feathers, distributing

an oil that keeps them waterproof. They will also fluff themselves up to create even

more air pockets for insulation. Birds and mammals also build up extra fat layers

in the fall in preparation for cold weather.

Good insulation is key. Many mammals grow a thicker coat for the winter, comprised of long guard

hairs and shorter underfur that is designed to trap air. Birds also have multiple

layers of feathers. As anyone with a down jacket may know, down feathers provide great

insulation, but only when dry. Birds frequently preen their outer feathers, distributing

an oil that keeps them waterproof. They will also fluff themselves up to create even

more air pockets for insulation. Birds and mammals also build up extra fat layers

in the fall in preparation for cold weather.

Countercurrent heat exchange helps many birds and mammals endure wading in frigid water or walking in the snow.

Through counter-current heat exchange, arteries (taking blood away from the heart) and veins

(bringing blood to the heart) run adjacent to each other. Heat is exchanged from warm

arterial blood to the cold blood in the veins, preventing cold blood from circulating

through the body and vital organs. In this exchange the arterial blood is also slowly

cooled down, meaning it loses less heat to the environment when it reaches the extremities.

counter-current heat exchange, arteries (taking blood away from the heart) and veins

(bringing blood to the heart) run adjacent to each other. Heat is exchanged from warm

arterial blood to the cold blood in the veins, preventing cold blood from circulating

through the body and vital organs. In this exchange the arterial blood is also slowly

cooled down, meaning it loses less heat to the environment when it reaches the extremities.

Changes in hunting and foraging behavior can help animals contend with food scarcity. Animals that are typically nocturnal, such as otters and great-horned owls, may become more active during the day. Typically very social creatures, otters also become more solitary over the winter, spreading out over larger distances in their search for food. Other animals will alter their diets over the winter based on food availability. Aquatic grazers such as swans are more likely to forage on land. Chickadees, who are mostly insectivorous, rely heavily on seeds, fruits, and even animal fat over the winter.

Food caching allows animals to have a reliable food source throughout the winter. Beavers will

collect branches that they stick into the mud underwater near the entrance of their

lodges. The cold water and ice act like refrigeration, keeping their food fresh. Up

in the alpine zones, pikas survive off of "hay piles" comprised of plants they gathered

in the summertime. Some birds, like Chickadees and Clark's nutcrackers, spend the

fall hiding seeds in various locations. When winter rolls around, they rely on their

excellent memory to find these food caches.

Winter Birding

Have you been wanting to try out birding? You don't need to wait until spring. In fact, winter can be a great time to practice your birding skills. With less birds around, the task of narrowing down possibilities can be less daunting, and it is significantly easier to spot birds in leafless trees. Winter birding is also a great way to get acquainted with year-round feathered residents.

It can also provide opportunities to spot rare birds, like irruptive migratory species. These are birds that tend to migrate only short distances, but given the right conditions, they will travel to much further wintering destinations. The conditions leading to such irruptions vary for different species, but often includes natural fluctuations in food supplies like cone crops.

A great place to begin with winter birding is your backyard. Bird feeders will help entice birds for easy viewing. As an added benefit, you will be doing birds a favor. Feeders are visited year round, but they can be especially helpful in the winter time when other food sources are not as readily available. Try out different seed mixes to see what birds show up. Suet also makes for a nice winter treat for birds, providing them with much needed fat and calories.

You can check out more beginner birding tips on our website.

Phenomenal Bird Brains

Clark’s Nutcrackers have a specialized pouch under their tongue that they use to transport up to 100 seeds at one time. By the time winter hits, they can have cached over 30,000 seeds in different sites with about 5 seeds each. Thanks to their impressive memory, they are able to find about 10,000 of these sites in the winter. Those that are forgotten about have the chance to grow into trees. White bark pines rely on the occasional forgetfulness of these birds.

Chickadees also have an excellent memory for their cached food stores. Compared to other birds, they have a relatively large hippocampus, the area of the brain used for memory storage. Studies have shown that every autumn, as they are caching food, chickadees regenerate neurons, allowing old information to be replaced by new information. They use visual and spatial cues to remember the exact location of many of their cache sites.

Updates from Lakeview Elementary

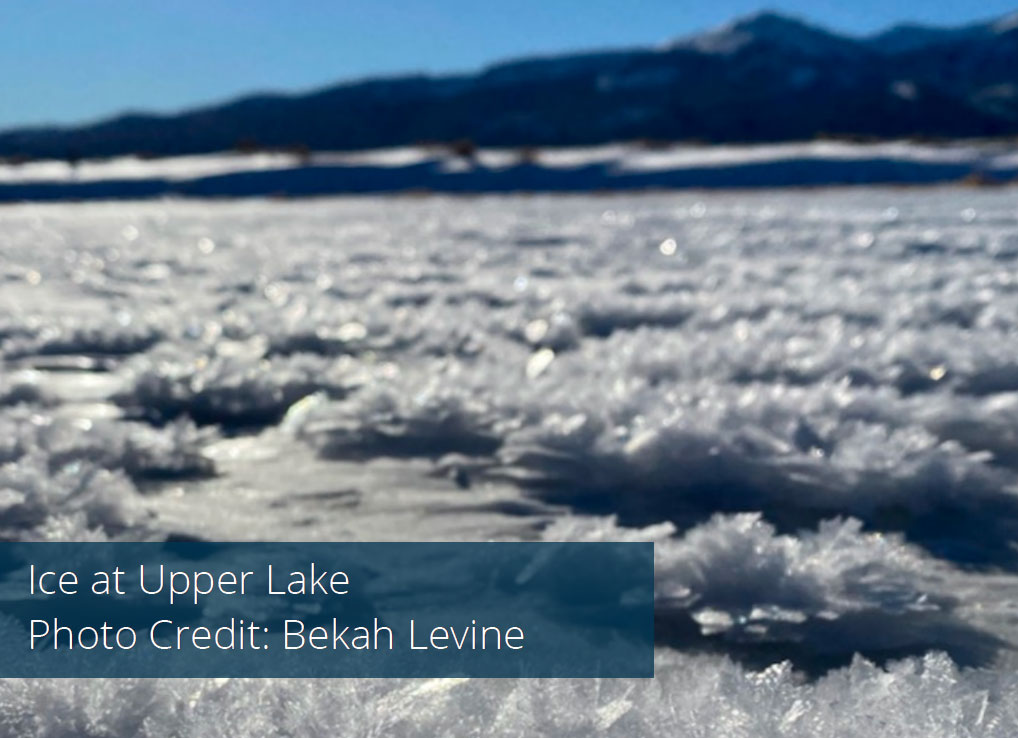

"In the Centennial Valley, the last days of autumn have been consistently cold (highs in the 20s F with nighttime lows below 0 F) but without much snow. A few inches have fallen in the past few days as we look ahead to the first official day of winter next week.

While many wildlife species of the Centennial Valley are either seasonally resident or engage in some form of hibernation, one species that remains, and is highly visible in snowy conditions, is the moose (Alces alces). Unlike species that are primarily grazers (e.g., deer and elk), moose are browser. They can still access willows, their primary food source, when snow is deep. In fact, moose numbers increase in the winter due to the high abundance of willow dominated habitat, which provides winter habitat for moose that summer at higher elevations nearby. A group of moose was recently sighted near Lakeview including a cow, two calves, and a bull with antlers. At this time of year, bull moose begin losing their antlers. This bull, nicknamed 'Lord Lopside', was remarkable in that his antlers were asymmetrical. This usually occurs due to injury during antler development.

Another species able to adapt to winter conditions in the Valley is the red fox (Vulpes vulpes). Fox rely on their keen senses of hearing and smell to alert them to the presence of subnivean prey (e.g., mice, shrews, and voles)."

Contributed by Gillian Hadley and our friends at Lakeview Elementary

Check out more pictures and videos from Odell Creek, and our other trail talks,

on our Instagram page @uofutaftnicholsoncenter. Happy trails!